The Learning Management System in Real Life

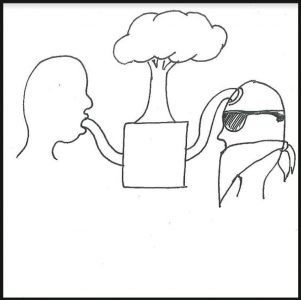

Unknown Strangers in the Classroom

Imagine yourself walking into a classroom. At the front of the room, your instructor is seated with six other people. These people have clipboards, stopwatches, and take extensive notes. Unlike your instructor, the identities of these six people are unknown; they’re all wearing masks.

As you enter, the group of unknown strangers asks for your identification. They write down your name, your major, your year of study, and what you’re wearing. They don’t introduce themselves, but maintain a steady gaze in your direction.

You become concerned about this invasion on your privacy and ask the instructor about these people.

“I don’t know who they are,” the instructor responds. “But I’m told that they’re here to help you.”

“Who told you that?” you ask, while the pens of the unknown strangers furiously record your conversation.

“They did,” the instructor says, motioning towards the unknown strangers.

You decide to take your seat in the classroom. As you do, the unknown strangers observe and record your behaviour. They write down the time you entered and where you sit. They record the time that passes while you’re sitting there. Then, when you speak to the student seated next to you, they record what you’ve said.

The next time the instructor walks near, you ask quietly: “Why do they need all this information and what are they going to do with it?”

“I don’t really know,” the instructor says. “I’m able to see some of what they’re recording, but after a while they’ll hide that from me. They’re also watching and recording what I do, too.”

The instructor returns to the front of the room. Concern over the presence of these unknown strangers has upset the atmosphere of learning in the classroom. Another student asks if we can see what the unknown strangers have written.

There’s a grumble from the unknown strangers, who huddle together for a moment. A brief conversation occurs that’s inaudible. After they reach a consensus, they slide a note over to the instructor.

“I don’t think so,” the instructor says, looking at the note. “They say it’s very complicated and troublesome to show you. They think it would be better if you just left them to do their work.”

Your instructor announces that there’s class materials available at the front of the room. Several piles of readings and assignments are stacked on the table. As you get up from your seat, the unknown strangers take note of the time and the path you take to the front of the room. As you begin collecting the class materials, they record the order in which you select them and how long you hold them in your hands before putting them down.

Eventually, you become overwhelmed by the presence of these unknown strangers and the information that they’re recording. You ask the instructor: “Can’t we make them leave?”

“No, this is their classroom,” the instructor says. “They built this classroom and control it. I’m just an invited guest and, like you, I’ll be kicked out as soon this course is over.”

Why is it that, in real life spaces, this kind of tracking seems completely inappropriate and creepy, whereas in digital spaces pervasive tracking is easily overlooked? The detailed tracking of student’s behaviour within Learning Management Systems already takes place, yet the scenario described in embodied terms sounds like science fiction.