The Tyranny of Convenience

Tim Wu (2018)

________

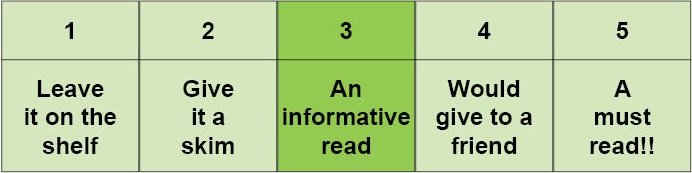

Digital Tattoo Rating: 3/5

Summary

The name Tim Wu might sound familiar: Wu coined the term “net neutrality”, which we reported on in February. He is a professor of law at Columbia University, ran for the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governorship of New York, and served in the office of the New York attorney general. If that didn’t keep him busy enough, Wu has written multiple books and articles educating us all on the intricacies of modern life. In short, he’s kind of a big deal. In his opinion piece for the New York Times, Wu discusses the convenience trap and what we can do to get out of it.

The Top 5

1. What is Convenience

Modern day convenience is about making our lives easier than ever. Wu points out that our economy is based on ease: when we find a company that makes our lives easy, the path of least resistance is to be loyal to that company. Creating loyalty based on convenience and ease is seen not only to be beneficial for consumers, but also for companies. Amazon and Apple demonstrate the benefit of supporting consumer ease through their race to become the first trillion dollar company.

2. The History of Convenience

It all started with “industrial efficiency”. In the late 19th Century, industrial efficiency trends began to adapt for household use, and the rise of household efficiency products took North Americans by storm. Fast food and household appliances are both products of this convenience revolution. The theory was that if you can complete inconvenient tasks more quickly, you will have more time for you.

But, the rise of individualism challenged convenience. As Wu writes “[c]onvenience meant conformity” (2018), and in the 1960s, more and more North Americans wanted to feel unique, heard, and identifiable. This couldn’t be done if everyone was using the same convenience products… could it?

3. The Convenient Self

The “second wave of convenience technologies” (Wu, 2018) blends the original mandate of convenience with the desire for individuality and self expression. The convenient self is supported by social media websites, music listening tools, video streaming sites, etc. Each of these technologies make it easier to be uniquely us, as long as we follow the terms, formats, timelines, and requirements of the mediating technology. Wu writes: “The paradoxical truth I’m driving at is that today’s technologies of individualization are technologies of mass individualization. Customization can be surprisingly homogenizing” (2018).

4. Expecting Ease

The more we become accustomed to the easy of modernity, the more we come to expect it everywhere. When the wifi stops working, or the Starbucks line is too long, we become irritated and try to subvert our discomfort. Discomfort is not easy.

Wu suggests that the toll of convenience culture is hardest on the young. Without having experienced much inconvenience, the feeling of waiting, working, or going out of one’s way, are not only challenging, but entirely foreign! Wu speculates that this may be the reason for low youth voter turnout in recent municipal, provincial, and federal elections. If you are not accustomed to waiting in line, the act of waiting to vote can be an enormous deterrent and barrier to entry.

5. Embracing Inconvenience

Wu invites us to “embrace inconvenience” (2018), and recognize that there is value in struggle. We often derive the most pleasure and fulfillment out of activities that require deep effort, dedication, and concentration. Wu isn’t suggesting that we abandon all ease and begin living in caves, but encourages readers to embrace difficult tasks that we enjoy (such as running, coding, learning a musical instrument or a language, or any other activity that challenges your brain, body, and spirit). The act of voluntary participation in difficult tasks can lead to can lead to revolutionary personal and social fulfillment.

Final Thoughts?

As convenience culture becomes more and more ingrained in the fabric of our lives, I wonder what types of activities count as revolutionary discomfort and inconvenience. Does the school work that I do for my degree count at inconvenience? What about the hours I spend volunteering to supplement my work experience? I recently went to a knitting party with some friends, and we spent an evening away from our phones drinking wine and learning how to knit. Would that count as inconvenient? At the time, it felt deeply convenient, because while our hands were busy with the soothing, repetitive task of knitting, we were able to disconnect and spend the evening chatting and sharing stories from our week.

Ultimately, I think this article left me with more questions than answers. Perhaps it’s a product of the genre of article Wu was writing, or perhaps it was a choice made by the author to force the reader to critically engage with convenience culture. Either way, this article has given me a lot of chew on, and I hope that you find it as interesting as I have.

What Do You Think?

Want to see more article reviews by Digital Tattoo? Have you read something recently that’s worth sharing? Let us know in the comments below or on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram!