Shareveillance: The Dangers of Openly Sharing and Covertly Collecting Data

Clare Birchall (2017)

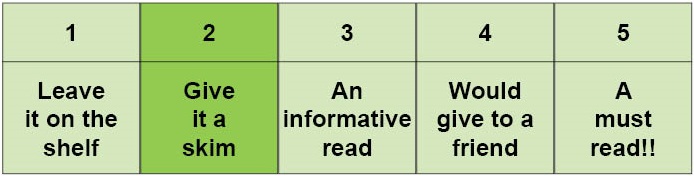

Digital Tattoo Rating: 2/5

Summary

What does it mean to share in the Digital Age? In her book Shareveillance: The Dangers of Openly Sharing and Covertly Collecting Data, Clare Birchall investigates the intricacies of digital sharing on personal and state levels, and attempts to find out who is benefitting from all of our collective data.

The Top 5

1. What is -veillance? (Chapter 1)

Birchall is a Critical Theory scholar who posits that contemporary ‘sharing culture’ is enabling surveillance. This book focuses on the idea that by posting our data on social media sites, and by having our information collected by data professionals, we are becoming a society of aggregate data points instead of individuals. This in itself is not what bothers Birchall, instead, the trouble is in the inequity between the data that we make available, and the data that is made available to us. “Government practices that share data with citizens involve veillance because they call on citizens to monitor and act on that data – we are envisioned (watched and hailed) as auditing and entrepreneurial subjects” (Birchall, Chapter 1*). Shareveillance is the state in which the government is able to aggregate and use our data, without having to share data in return. Indeed, Birchall goes so far as to theorize that the small amount of data provided to us by the government is purposely made public, not for public good, but as incentive for the public to give-up even more of their data. Confused? So was I. Let’s break these concepts down a bit.

2. Data (Chapter 2)

The trouble with data is that it isn’t neutral. We like to think that it is, but an entity’s access to data can contribute to their agency. For example, if one country has access to the polio vaccine, and another country doesn’t, the country that can eradicate polio has an advantage over the country that can’t. The same can be said on an individual level. Someone with access to data may inherently have an advantage over someone who does not. By giving governments and organizations access to all of the public’s data, while receiving little in return, we are giving them an advantage over us.

3. Open & Closed Data (Chapter 5)

Open data is data that had been made available for public use. Examples of open data include the City of Toronto’s Annual Energy Consumption Report (via the City of Toronto’s Open Data Catalogue), and Graffiti Site Data(via the City of Vancouver’s Open Data Catalogue).

Closed data is data that has not been made available for public use. Examples of closed data include security files, defence strategies, etc. When a hacker or whistle-blower like Edward Snowden releases ‘government secrets’, they are releasing closed data to the public. The difference between open and closed data is significant, because it signals what information we, as a public, have access to. The information that we have access to directly impacts the political agency that we have.

Birchall explains that while we like to think of open data practices as ‘good’, and closed data practices as ‘bad’, even open government data is not neutral. Birchall’s book explores the ways in which open data provided by government organizations can be used as a lure for individuals to give up more of their own data, and how challenging it can be to make sense of the massive quality of poorly organized data made available to publics. Neutrality and accessibility are not guarantees in open data practices.

4. Citizens as Data (Chapters 3 & 4)

Birchall is skeptical of hyper-connectivity and current government open-data practices. The concern is that through data-professionals’ ability to aggregate and profit from our data, our value as citizens is not in our ability to meaningfully contribute to democracy, but instead our ability to contribute to data sets. Birchall worries that by reducing the public to data sources, the public will, in turn, lose its political agency. This is further complicated by failings of the open and closed data system in which data is withheld from the public, or made available in ways that are not neutral or accessible.

5. So, What Now? (Chapter 6)

How do we get out of the trap of becoming non-agent citizens for overly surveillant capitalist governments and organizations? Well, the short answer is that we have to take it one step at a time. Birchall suggests supporting hacking, whistle-blowing, and open-data initiatives. On a smaller scale, Birchall focuses on the importance of grassroots movements (like U of Ts Guerrilla Archiving event), and the significance of informed choices by an educated public. Try out de-centralized storage for your files, using encryption technology, and ensuring your right to opacity by using services that limit how much of your data is shared. By making small changes, and keeping aware, you can “cut” into the system of shareveillance and ensure equitable access to information, as well as the right to keep your information opaque.

Conclusions

While this book was a very interesting read, it was really dense. Birchall rushed through topics in the interest of keeping the book short (86 pages), but sacrificed accessibility. While the information in this book could be a wonderful tool for young adults who are digitally and politically engaged, the barrier to entry makes this book relatively inaccessible for the average undergraduate student. Further, the examples given are specifically for professors and long-time scholars. While writing a book by scholars, for scholars is not inherently negative (and I recognize that the goal of the book was not to cater to young adults), I feel that making a longer, more accessible version of this book would be of great benefit to scholars, students, and young adults alike.

*This book was read as a digital copy and therefore did not have accurate page numbers. This review will use chapter numbers for citation purposes.