Have you ever been guilty of texting at the dinner table, checking your notifications when hanging out with friends, or having trouble falling asleep without your phone in your hands? You may be an unknowing victim of screen addiction.

What is Screen Addiction?

Screen Addiction is described by Balhara, Verma, and Bhargava (2018) as “the engagement with a variety of screen activities in a dependent, problematic manner”. Addiction is defined by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as a “maladaptive pattern of substance use, leading to significant psychological impairment” (Bian & Leung, 2015, p.62). As such, addiction to screens can lead to a loss of control in regulating screen use, feelings of dependency and mental preoccupation/compulsion with screen activities, and signs of withdrawal and negative effects when not engaging in screen activities.

Implications of Screen Addiction

Screen addiction takes a toll on your health, and has both physical and mental effects on your body. These effects include tiredness, increased stress, and a shortening of attention span. This list is far from comprehensive, but aims to review the literature surrounding some of the damaging effects of screen addiction to your physical and mental health.

Physical Implications

Fatigue

Looking at your smartphone for extended periods of time can lead to fatigue and tiredness, especially in the muscles of the neck and spine, due to the forward head posture used in smartphone viewing. Seong-Yeol Kim and Sung-Ja Koo tested the level of fatigue in the neck of people that used smartphones for 10, 20, and 30 minute intervals in their research for the Journal of Physical Therapy Science. They found that smartphone users developed fatigue in the left cervical erector spinae and the left and right upper trapezius muscles after 20 minutes of continuous smartphone use.

“Smartphone overuse places the head in an unvarying posture and that continuous muscle contraction then brings about muscle weakness and fatigue that could easily develop into chronic cervical pain” (Kim & Koo, 2016, p.1671).

Esotropia

Esotropia is a disorder in the alignment of the eyes in which one, or both of the eyes are turned inward. Lee, Park, and Heo published a study in 2016 on the correlation between smartphone use and Acute Acquired Comitant Esotropia (AACE) in BMC Ophthalmology. They studied 12 adolescent patients with AACE and tested to see if a reduction in smartphone exposure affected the degree of esodeviation, or inward-ness of the eyes. They found that a one month restriction in smartphone usage resulted in a decrease in esodeviation for all patients studied. The researchers postulate that smartphone usage, especially at a young age, can contribute significantly to the development of esotropia.

“Smartphone restriction led to a significant decrease in esodeviation in all patients. Therefore, we speculate that excessive smartphone use could lead to the development of AACE” (Lee, Park, and Heo, 2016, p.6).

Wrist and Finger Injury

Physical injury to the wrist and fingers can also occur as a result of excessive smartphone usage. Twenty six participants were studied by Hong et al. and were asked to type out the same document to a smartphone, varying in holding the phone with one hand and two hands. They controlled the experiment by varying the groups that began typing with one hand or two first. They found that extensive one-handed usage of smartphones led to higher muscle activity and a higher risk of musculoskeletal disorders than two-handed smartphone usage. They state:

“When using a mobile phone for notes, text-messaging and creating documents etc., most mobile phone users had active use of the thumb [9]. According to a study on the repetitive movements of the thumb, when on work duty without enough rest, such movements can cause osteoporosis of the thumb [17]. Quick and repetitive movements of the thumb likely increase a possible exposure to De Quervain syndrome [7]. Therefore, inappropriate over-use of a smartphone presents a high risk of a musculoskeletal lesion in the thumb” (Hong et al. 2013, p.474).

Neck and Spine Injuries

An important physical implication of the over-usage of smartphones is the risk of neck or spine disorders due to improper posture while holding a device. Kee et al. found that the posture for smartphone use, consisting of holding a smartphone and looking down at the screen of the device, lead to “a more flexed craniocervical posture” (Kee et al., 2016, p. 344). In the posture for cellphone use, there is more load on the trapezius and cervical vertebra erector muscles than in a neutral posture. Kee et al. found that the cervical load increases from about 10 pounds in the neutral position to 60 pounds at 60 degrees. They state:

“This study found that the cervical range of motion of the smartphone-addicted teenagers significantly decreased in almost every direction. This finding suggests that smartphone addiction has a deleterious influence on craniocervical mobility” (Kee et al., 2016, p.344).

Phantom Vibration Syndrome (PVS)

Some smartphone users have reported an interesting phenomenon of perceiving the sensation of the vibrations caused by a smartphone, even when a smartphone is not present. This phenomenon was coined ‘Phantom Vibration Syndrome’ by a columnist named Robert D. Jones in 2003. In a literature review, Shatrughan Pareek cited several studies over a period from 2010 – 2017 by researchers in different areas of the world. In each of these studies, 56% to 85% of participants reported perceiving Phantom Vibration Syndrome during daily living.

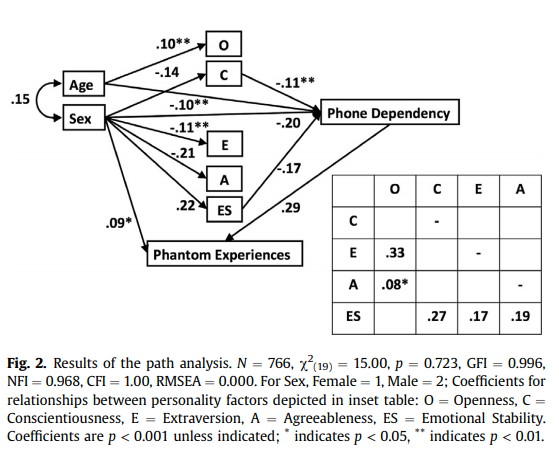

In a 2017 study by Daniel J. Kruger and Jaikob M. Djerf in Computers in Human Behaviour, they found that phone dependency symptoms predicted the frequency of phantom cell phone experiences. They postulate that this correlation is due to psychological dependency, as “one of the psychological features of addiction is hypersensitivity to stimuli similar to the ones that are rewarding” (Kruger &Djerf, 2017, p. 362). As users increase the duration of cell phone use, they may become more sensitive to the stimuli of muscle contractions that are similar to cell phone notifications.

Results of Kruger & Djerf’s study of cell phone dependency and PVS (Kruger &Djerf, 2007, p.363).

Mental

Increased Stress

In a study involving 293 university students, Samaha and Hawi sampled the smartphone usage and perceived stress of the students using self-reported measurements. They employed the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) and Smartphone Addiction Scale – Short Version (SAS-SV) and analyzed the results for correlation. They found that an increased measure of smartphone addiction correlated to an increased measure of perceived stress, without a change in other measures. Samaha and Hawi characterize the relationship between the two variables as a positive feedback loop:

“For instance, the higher the risk of smartphone addiction is, the higher the level of perceived stress would be, and the higher the level of perceived stress is, the higher the risk of smartphone addiction would be. In other words, anything that raises the level of perceived stress might increase the risk of smartphone addiction” (Samaha & Hawi, 2016, p.324).

Lower Mental Acuity

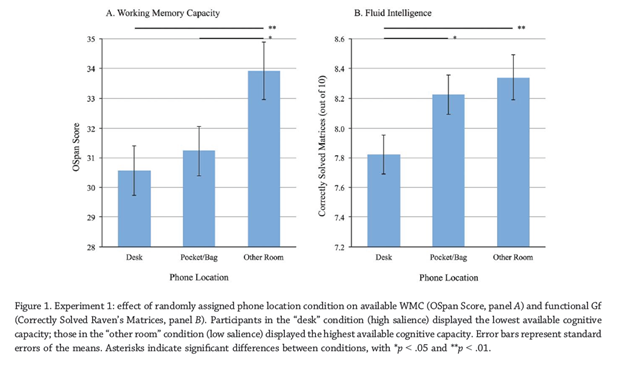

In a study published in The Consumer in a Connected World, Ward et al. found that the mere presence of a smartphone reduces a person’s working memory capacity and fluid intelligence. Working memory capacity is defined as “availability of attentional resources, which serve the “central executive” function of controlling and regulating cognitive processes across domains” (Ward et al., 2017, p.141). Similarly, fluid intelligence is defined as “the ability to reason and solve novel problems, independent of any contributions from acquired skills and knowledge” (Ward et al., 2017, p.141).

They sampled 548 undergraduate students while varying the placement of smartphones in another room, in a bag, or at the desk where they sit. Each group of participants were then instructed to complete a series of math problems, pattern recognition questions, and memorization tasks. Unlike other experiments, Ward et al. did not send notifications to the phones during the tasks, and made sure that they were silenced and vibration was turned off. Even under these conditions, they found that the performance of each of the groups to be significantly different, improving as the phone was placed further away.

Ward et al.’s data analysis of the performance of each of the student groups (Ward et al., 2017, p.145).

“The mere presence of participants’ own smartphones impaired their performance on tasks that are sensitive to the availability of limited-capacity attentional resources (Ward et al., 2017, p.146).

Shortening of Attention Span

Another important consequence of smartphone addiction is the reduction in one’s attention span. Jeremy Marty-Dugas of the University of Waterloo sampled 157 undergraduate students to analyze the relationship between smartphone usage and everyday inattentiveness. Marty-Dugas employed self-assessment questions for both measures. He found that higher frequency of smartphone use increased inattention across four measures of attention: Attention-Related Cognitive Errors, Mindful Attention Awareness, Spontaneous Mind Wandering, and Deliberate Mind-Wandering.

“Importantly, the frequency of absent-minded smartphone use predicted everyday attention errors and spontaneous mind-wandering independently of individual differences in absent-mindedness, confirming that our measure of absent-minded smartphone use was not simply redundant with our measure of general absent-mindedness” (Marty-Dugas, 2017, p.15).

Feeling of Missing Out (FOMO)

A consequence of mediating social relationships with smartphones includes the development of a new kind of phobia. Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), or nomophobia, is defined as “a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent” (Beyens, Frison & Eggermont, 2016, p.1). In a 2016 study published in Computers and Human Behavior, Beyens, Frison, and Eggermont conducted a study on the relationship between FOMO and Facebook use. They sampled 402 high school students using self-reporting measures. They employed the Fear of Missing Out Scale to measure FOMO and the Facebook Intensity Scale to measure the frequency of Facebook use. They discovered that a high measure of FOMO correlated significantly with a high measure of Facebook use, with a p-value less than 0.01:

“Second, fear of missing out was significantly associated with Facebook use. More specifically, the results indicated that adolescents who experienced more fear of missing out, reported a higher Facebook use (Beyens, Frison & Eggermont, 2016, p.5).

Reducing Your Screen Addiction

So how can you fight back against screen addiction? Here is a quick four-step guide to help you get started. Remember, the only one who can change you is yourself, so stay committed and keep your goals in mind, and good luck!

1. Admit the Problem

The first step in any recovery is to admit the problem. If you think you are addicted to your smartphone, you can begin the reconciliation process by admitting that the problem exists.

2. Set a Timer for Screen Use

Setting up a timer for certain applications, or for smartphone usage in general, can help to explicitly track your smartphone screen time. In July 2018, Facebook and Instagram launched a feature to track screen time [1][2]. On iOS 12, a new native feature helps to track your screen time and displays screen time per app category [3]. On Android, there are apps like Screen Time Parental Control [4] and AppDetox [5] to help you reduce screen addiction by removing access to certain apps.

3. Turn Off Notifications for Unimportant Applications

Referencing Kruger and Djerf’s study on Phantom Vibration Syndrome, we can reduce our sensitivity to the stimuli of our smartphones by reducing notifications to important applications, such as phone calls or text messages from family and friends.

iOS: You can turn off notifications temporarily using the Do Not Disturb profile, or Allow/Disallow Notifications separately for individual apps. Here are some guides on how to turn off notifications on iOS:

How to Turn Off Notifications on an iPhone – Digital Trends [6]

How to Turn off iPhone Notifications in iOS11 – Tom’s Guide [7]

Android: Android users have a slightly different method to adjust notifications of applications depending on the version of Android they are running. Here are some guides on how to turn off notifications for applications on Android, regardless of your version:

How to Turn Off Notifications in Android (Android 4.1 to 8.0) – Digital Trends [8]

How to Disable Notifications from Any App in Android (Android 4.1 to 8.0) – Make Use Of [9]

4. Exercise and Hobbies!

Lastly, another strategy to reduce smartphone addiction is to replace the time spent on the smartphone with other activities, such as exercise and hobbies. In the Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, Hyuuna Kim proposes that drumming, art, and exercise are valid forms of therapy for addiction rehabilitation.

By slowly replacing the time spent on the smartphone with other activities, one can eventually reduce the usage of smartphone-related activities to important tasks, and reduce the negative impacts of smartphone addiction in their everyday life!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not constitute legal or financial advice.

Always do your own research for informed decisions.

Image Credits

Computer Addiction Help – Alexas Fotos on Pixabay

https://pixabay.com/en/computer-addiction-help-1106899/

Sources / Articles You May Be Interested In

Balhara, Y. P., Verma, K., & Bhargava, R. (2018). Screen time and screen addiction: Beyond gaming, social media and pornography– A case report. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 77-78. Retrieved July 12, 2018, from https://www-sciencedirect-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/science/article/pii/S1876201818304453.

Bian, M., & Leung, L. (2014). Linking Loneliness, Shyness, Smartphone Addiction Symptoms, and Patterns of Smartphone Use to Social Capital. Social Science Computer Review, 33(1), 61-79. Retrieved July 31, 2018, from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0894439314528779

Kim, S., & Koo, S. (2016). Effect of duration of smartphone use on muscle fatigue and pain caused by forward head posture in adults. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 28(6), 1669-1672. Retrieved July 17, 2018, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4932032/.

Lee, H. S., Park, S. W., &Heo, H. (2016). Acute acquired comitantesotropia related to excessive Smartphone use. BMC Ophthalmology, 16(1). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4826517/.

Hong, J., Lee, D., Yu, J., Kim, Y., Jo, Y., Park, M., & Seo, D. (2013). Effect of the Keyboard and Smartphone Usage on the Wrist Muscle Activities. Journal of Convergence Information Technology, 8(14), 472-475. Retrieved July 17, 2018, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4499974/.

Kee, I., Byun, J., Jung, J., & Choi, J. (2016). The presence of altered craniocervical posture and mobility in smartphone-addicted teenagers with temporomandibular disorders. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 28(2), 339-346. Retrieved July 24, 2018, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27065516.

Pareek, S. (2017). Phantom Vibration Syndrome: An Emerging Phenomenon. Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research, 7(4), 596-597. Retrieved July 31, 2018, from http://ajner.com/AbstractView.aspx?PID=2017-7-4-28

Kruger, D. J., &Djerf, J. M. (2017). Bad vibrations? Cell phone dependency predicts phantom communication experiences. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 360-364. Retrieved July 31, 2018, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563217300171.

Samaha, M., & Hawi, N. S. (2016). Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior, 57, 321-325. Retrieved from https://www-sciencedirect-com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/science/article/pii/S0747563215303162

Ward, A. F., Duke, K., Gneezy, A., & Bos, M. W. (2017). Brain Drain: The Mere Presence of One’s Own Smartphone Reduces Available Cognitive Capacity. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(2), 140-154. Retrieved from https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/691462.

Marty-Dugas, J. J., & Smilek, D. (2017). The relation between smartphone use and everyday inattention (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Waterloo. Retrieved from http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-40489-001

Beyens, I., Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2016). “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 1-8. Retrieved August 2, 2018, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563216304198.

Kim, H. (2013). Exercise rehabilitation for smartphone addiction. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation, 9(6), 500-505. Retrieved August 2, 2018, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3884868/.

Other Sources

Facebook and Instagram Now Show How Many Minutes You Use Them – (TechCrunch)

https://techcrunch.com/2018/08/01/facebook-and-instagram-your-activity-time/

iOS Native Screen Time Manager (Apple) – https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2018/06/ios-12-introduces-new-features-to-reduce-interruptions-and-manage-screen-time/

Android Screen Time Parental Control app (Google Play) – https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.screentime.rc&hl=en

Android AppDetox app (Google Play) – https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=de.dfki.appdetox&hl=en_CA