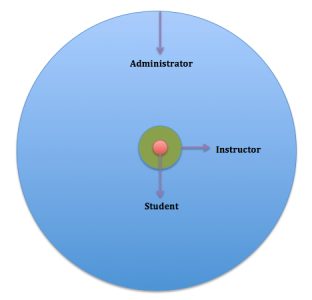

As I continue waiting for the return of my data from UBC’s Office of Counsel, I’ve begun examining the structure of the Connect system. For a Learning Management System, Connect effectively manages the amount of information that students can learn from it. The  system is divided into three roles: that of the student, who creates the majority of the data but can only view a minority of the analytics, like grades; that of the instructor, who can view much more of the analytics than a student can, but is limited to the students within the courses they teach, and those analytics that reference the specific courses that they’re teaching; and that of the administrator, who can view all of the student and instructor data across all of the courses on Connect. It would seem to me that Connect serves to benefit the administrator most particularly.

system is divided into three roles: that of the student, who creates the majority of the data but can only view a minority of the analytics, like grades; that of the instructor, who can view much more of the analytics than a student can, but is limited to the students within the courses they teach, and those analytics that reference the specific courses that they’re teaching; and that of the administrator, who can view all of the student and instructor data across all of the courses on Connect. It would seem to me that Connect serves to benefit the administrator most particularly.

Unequal Terrains

The graphic on the above right represents the hierarchy of access created by the Connect system. It is biased towards the administrator, illustrated in blue, who can access all of the student data across every course for an indefinite amount of time. The instructor, like the student, has a limited capacity of access. They can only view data that pertains to the students currently enrolled in their course(s) and their timeframe of access is limited to the period when that course is in session. The student, who is represented in red and creates the vast majority of the data in the Connect system, has very limited access to the analytics. In fact, the only data that is viewable for students is likely the grading area, where a student can view the grade they’ve received for a particular assignment, and perhaps view how assignments are weighted towards their final grade. In this way, the architecture of the Connect system is similar to the panopticon, an institutional design intended mainly for prisons, where inmates are spread in a circular formation and monitored from a single tower at its centre. Because the prisoners are unaware of when the tower is occupied, and where the guards limited attention is focused, they feel as if they are always under surveillance, despite not necessarily being constantly watched, and thus, conform their behaviour accordingly.

A Machine Shrouded in Secrecy

How do you feel about being such a small cog in a big machine? If the Connect system is supposedly encouraging learning and helping students, then shouldn’t students have some access to the analytics that instructors and adminstrators are viewing? Learning Management Systems operate at a huge expense under the pretense of encouraging learning, yet Jesse Stommel, the executive director of the Division of Teaching and Learning Technologies at the University of Mary Washington, has this to say about them:

“The LMS can’t ensure that students will learn … [it] will, however, ensure that students feel more thoroughly policed … How will learning be changed when everything is tracked? How has learning already been changed by the tracking we already do? When our LMSs report how many minutes students have spent accessing a course, what do we do with that information?”

Mr. Stommel is asking the same questions that I am. Just because we can do something, doesn’t mean that we should; just because technology has advanced to a point where mass surveillance and data collection are possible, doesn’t mean that we have to monitor and record everything, like the online behaviour of students. There are risks in collecting and storing this data that far outweigh the current benefits, which might be none. It’s tough to say how valuable this data might be because we’ve never seen it before. But stick around, I’ll be revealing everything that the Connect system collects in the next couple of weeks.

“Blind Cogs and Pinions”

I’d like to close with two more quotes, the first is provided by Mr. Stommel and is from the 1915 book, Schools of To-Morrow, by John Dewey:

“Unless the mass of workers are to be blind cogs and pinions in the apparatus they employ, they must have some understanding of the physical and social facts behind and ahead of the material and appliances with which they are dealing.”

We as students are the “blind cogs and pinions” and the “apparatus they employ” is Connect. We don’t know what information is being collected, we don’t know why it’s being recorded, we might not even know that it’s happening, and, most frighteningly, we might not even care. If the system is going to provide any benefit to us as students, then we must have some understanding of its workings, if not for the production of meaningful consent, then for the functioning of its stated goal: to encourage learning.

The final quote is by David Cameron, former prime minister of the United Kingdom, who asked this question in 2009 about the power of government surveillance and data collection:

“How have we got ourselves into the position where there is such a marked imbalance of power between the citizen and the state?”

At UBC, we’re not being monitored to the same extent as the international security measures that Mr. Cameron is remarking upon, but the power imbalance is very much the same. We as students take the role of citizens in this analogy and the state is UBC’s administration: we don’t know why or what is being tracked and we’re told that it is for our own good. This rhetoric is eerily similar to what the United States’ National Security Agency might tell a concerned citizen who voices an objection about how the Patriot Act is infringing on their personal freedoms by performing wiretaps and invasive search and seizure measures. It is also reminiscent of the dystopian future that George Orwell predicted in his novel 1984. We cannot passively trust that Big Brother is watching and looking out for our best interests; we must actively ensure that our best interests are being protected in this new era of digital surveillance.

If you missed them, check out my blog posts on what Learning Management Systems are capable of, how Connect seems to be breaking BC’s privacy laws, and how Connect’s Terms of Use are an unethical means of producing consent. Now that you understand a little bit more about the roles within Connect, how does it feel to be a part of it?

The Blog Series

The Connect Exposed blog series documents my inquest into data collection on Blackboard Connect, the difficult process of obtaining my data from UBC, and privacy concerns around the collection of student information.

Your post made me think about the following quote:

“What I realize now is that by directing our students to adapt to a world in which they can exercise no control over their environment, where every click and eyeball twitch is monitored and analyzed by inscrutable algorithms, we are in fact preparing them for the real world of work (and society) that they will be living in. The Learning Management System is in fact a near-perfect training ground for the life that awaits them.”

— http://abject.ca/wrong-about-the-lms/

Hi Hank,

I really appreciate you sharing that quote and article. I can’t help but get the sense that the writer is being sarcastic and not just cynical. If the LMS is the perfect training ground for the imperfect world, then it’s treating a symptom and not addressing the disease. The real of world of work does not have to be—and quite often isn’t—like the scenario described in the article. (It does provide a nice analogy to the LMS, however.) And if the world of work is moving towards that level of surveillance, and is removing the agency of its participants, then we’re moving in the wrong direction as a society. This is what we need to be fighting against, not reinforcing in the tools that students, including myself, are being forced to used. Thanks for sharing!

Bryan