The 30 business days that FIPPA allows for a public body to provide personal information expired on August 19th, 2016. I reached out to the University Office of Counsel and asked them when I was going to receive my data, and was informed that because of the “large volume of responsive records” that they’re dealing with, they’ve opted to extend the deadline by an additional 30 business days. There’s not too much I can do but continue waiting.

To me, this is another reflection of a broken system. Throughout this process I’ve met resistance because of the measures I choose to exercise in my search to understand what data Connect is collecting and retaining, and I’m interpreted as a meddling, bothersome nuisance. And perhaps I am. But it isn’t my fault, or really even my concern, if there isn’t functional protocol in place to address the requirements of privacy legislation. The system was broken before I got involved; I’m just the person who leaned on it and made it topple.

In the meantime, I’ve been researching the history of Learning Management Systems (LMS), how they came about, why, and where they might be going. (I credit a comment on my last Connect blog post for pushing me in this direction. And I find a great deal of solace in knowing that my criticisms of the LMS agree with larger conversations taking place in the community.) Historically, Universities were the first sites of the internet. In the mid-1990s, people began connecting over the web at Universities all across North America. The first websites were often faculty and student pages, and some of the first Wikis were launched at Universities and encouraged open collaboration between the local academic community and people from around the world.

But, as the internet began to grow beyond University campuses and extend itself into the public sphere, privacy concerns emerged. There was a growing worry that the information being shared by students was too accessible to the public, and there was a sense of fear about where this information was being stored, and what private corporations might be doing with it. Privacy laws formed that protected student data, and Universities were somewhat forced to insulate themselves from the public sphere of the internet. Instead of students and faculty collaborating on public websites, Universities created internal, online spaces that mimicked the external tools available.

The need for these services was two-fold: Universities felt pressure to protect student data and couldn’t actively encourage students to use resources that were privately held and collected personal information; but they also wanted to continue collaborating and using the tools that were created on the external internet. The software market sensed this conflict and offered a solution: The LMS was born. It offered to safely provide the public tools from the external internet on an internal network so that students and faculty could continue collaborating in a safe, sterile, and legal environment.

In theory, it was a great idea. But in practice, the end product couldn’t compete with the resources available on the public internet. How could it? No amount of funding is equal to the drive found in private industry and the innovation of open-source software. The LMS manufacturers made grandiose promises to Universities about the capabilities of their product to encourage learning through data collection and predictive analytics. However, all these features amounted to was creating an environment where students were heavily monitored and policed, not supported or encouraged. And the resources available, which supposedly emulated the public tools created by companies like Google and Microsoft, were watered down, ineffective, and inefficient. The LMS didn’t and doesn’t encourage learning; it only helps to meet privacy regulations.

And so we’re stuck here. Paying ridiculous amounts of money for the license to a product that doesn’t accomplish what’s freely available on the internet, doesn’t accomplish any of the associated learning objectives that might separate it from these free services. Its only benefit is that the data it collects is stored onsite to meet legal requirements. However, if this data is essentially useless, then what’s the point in recording it? Which means: Its sole benefit is entirely lost.

Students are likely already sharing and collaborating through free tools available on the public internet, anyways. Do you have a Google email account? Do you store documents in its Drive component and collaborate with peers using its Document feature? How about forums? I bet that students are more likely to post to Reddit than to any forum available on Connect. And I’d suspect, especially after reading this blog series and understanding the surveillance capabilities of Connect, that students are more comfortable sharing information on the public internet than they are on the LMS. And who could blame them: the LMS’s primary function is surveillance. Weren’t these the exact measures that the LMS was created to avoid?

So with this understanding of where the LMS comes from, I ask: Has it completely lost its purpose? If students are already engaging in these external resources and don’t have concerns over privacy, then shouldn’t Universities return to embracing these technologies instead of competing against them?

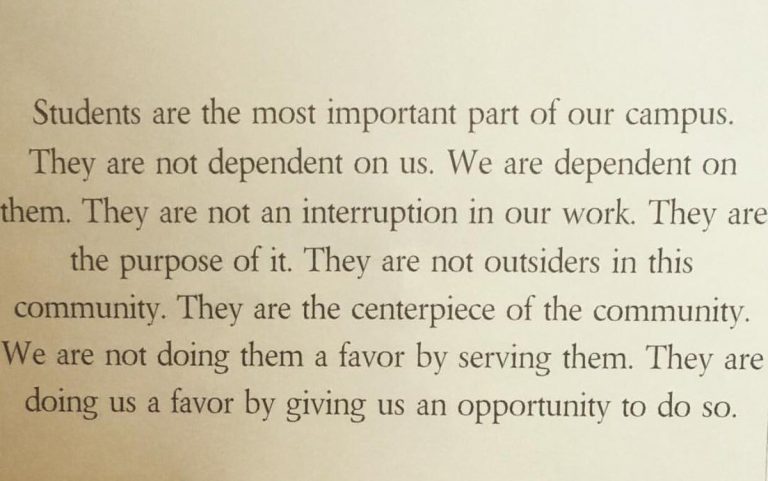

Posted on UBC President Santa Ono’s Twitter in August, 2016.

And to provide some further context for the image above: UBC President Santa Ono uses this image to remind himself of the true values a University should have. I believe that the adminstrators who are responsible for Connect, and the lawyers who drafted its Terms of Use, would benefit from considering the sentiment contained within this image, to be reminded of whom the LMS should serve.

The Blog Series

The Connect Exposed blog series documents my inquest into data collection on Blackboard Connect, the difficult process of obtaining my data from UBC, and privacy concerns around the collection of student information.

Hi Bryan,

This is such an interesting series – thanks for sharing your experience! I’m in Cindy’s camp. I can’t believe I’m saying something positive about the CMS/LMS industry, because those of us who work with them daily generally really dislike them to begin with. However, these tools have provided a means for instructors (who may not necessarily have any teacher training whatsoever, let alone training for teaching online or with digital tools, a task that is being asked of an ever-increasing number of faculty these days) to easily organize course content for students in a way that is easy to scale up and in a way that maintains some level of consistency from semester to semester, year to year, etc.

That said, one thing that is really lacking is the analytics that these systems provide. From my experience, beyond click logs and login tracking, the average CMS/LMS isn’t really doing too much for us, which is sad. I believe the data collection potential allowed by these tools offers a real opportunity for both students and instructors to learn about patterns of behavior and effectiveness of content. From an instructor’s perspective, being able to see what students are looking at helps them make better decisions about the usefulness of specific resources that have been provided in the course. Here is an example: I will often check access records of students for specific pages within an online course, and if I see that one page is getting TONS of clicks compared to the rest, that’s a flag to me. I’ll look at that page and try to figure out a reason why it’s being accessed so frequently. Depending on what that page of content contains, I may consider moving it to a more readily-available place, or adding additional resources about that topic to help students understand it better. For me, it’s less about “who’s doing what” online and more about “how is my CONTENT performing online?”

From the student’s perspective, it’s my personal belief that they should have access to their own data records. After all, it can help you make decisions about your learning behaviors as well, and there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be available anyway. Who is it hurting?

I can totally empathize with your position that grading students based on their patterns of access is not necessarily the best way to go about assessing learning, as well as your concern about the ethics behind WHY data is collected and HOW it is used. (I can also say that I disagree with participation grades in general – every student “participates” in a course in their own way, and just because one student’s method of participating doesn’t align with someone else’s belief about what “acceptable participation” looks like doesn’t necessarily mean that student isn’t learning. But that’s a discussion for another day.) All companies that collect data about aspects of their users’ lives (FitBit, Amazon, Google/Android, Apple, etc…) should be concerned about ethical use of that data, and you might be happy to know that it is a conversation that is lively and heated in the community.

Best of luck in your endeavor! I’ll be following along!

Hi Katrina,

Thanks for your thoughtful response and for reading! I do see the merit in collecting data and using it to inform the layout and organization of content to benefit students and to learn how they’re learning. I feel like the point of my exercise (in trying to understand how Connect is collecting information and what it’s being used for) is to open up a discussion between students and staff about learning analytics: how they’re operating and how they can be improved—and I’m glad to read that this conversation is already alive and well in the community.

That being said, I feel like there has been a lack of transparency on the part of UBC about learning analytics and the LMS. And maybe it’s not that they’re hiding anything, but just that students haven’t been aware enough to ask questions. I’m not really sure where I stand on the LMS. I realize that I’ve been quite critical, which is a reflection of my initial reaction when I discovered the surveillance taking place. And I’ve been talking with a lot of other students about this, and they’ve all had the same reaction of initial outrage: “They’re doing what!?” This is the lack of transparency that I think we can improve upon.

You might be interested to know that I received my data from UBC this past Friday, and I’ve been spending the last two days sifting through a small mountain of information. The amount of data that’s created from a one-minute interaction with UBC’s LMS, Connect, creates about 45 unique data points. That’s a whole lot of information in very short time. But like you said, what’s being done with it isn’t very interesting or useful. An instructor that I spoke with expressed her frustrations with the limitations on reporting tools available within Connect. But she did use them to calculate grades like participation. Like you said, it would be useful if students could also run the reports and see how they’re doing compared to their classmates.

So, perhaps, this is just a longwinded way of saying that my exercise, more than anything, is just a way of stating that we, as students, do care about learning analytics and are interested in being part of the conversation that’s happening about them. Data collection can be a good and useful thing; it can also be a bad and invasive thing: it just depends on the measures in place to protect everybody who is involved. Anyways, I’m going to be going through all the information UBC sent to me, and I’ll be posting something later in the week from what I’m able to discern, which will require some outside input. Thanks again for reading and sharing your thoughts! It’s so great to see the perspective of professionals working in this industry.

Bryan

Wow! Congrats on finally getting the data. I’m really looking forward to your thoughts on it all! Honestly, students becoming interested is the first step toward a more transparent implementation of learning analytics. It’s really good to hear that there are students who do care about these things and are also interested! Keep it up, and know that you have helped lay the groundwork at your institution to handle future data requests that may be require a more time sensitive turnaround – these issues are not going away so it will have been good practice for your university administrators.

Hi Bryan,

Really interesting series and account. I am curious if you ever got a copy of the records you requested?

Clint

Hi Clint,

I haven’t received a copy of the records yet. UBC extended the deadline until September 30th, 2016. So I should be receiving the records in the next week, provided they don’t file for an extension with the OIPC.

I’ll be writing another blog post when I hear back from UBC about my request, and whether or not my data is included in their response. Thanks for reading!

Bryan

Thanks for taking on such a complex issue that allows us to ride along as you claim ownership over your data (as it exists in the lms)! I can’t believe that I am about to defend the LMS (actually, I’m not), but I’d like to suggest a broader view of its purpose. The University is (as you allude to) legally bound – via our privacy laws: to offer online spaces for course activities that protect students’personal information . The “surveillance” aspect is an unfortunate side effect and is often lumped together under the more socially acceptable term “learning analytics”. There are many unanswered questions about learning analytics and how they could, should, would be best employed to better inform what we do to help students learn – but in the end – students benefit by being as well informed as possible so they can clearly exercise the right to choose how, when and by whom their data is collected and for what purposes. There’s alot riding on the checking of the “agree” button!